Is humanism an archaic way of life as the title of this article suggests? Perhaps it is worth reconsidering the question altogether. Thus, it may be worthwhile asking ourselves something akin to the following – is our way of thinking and behaving appropriate for the 21st century and beyond? The short answer to this is “no”. However, this answer is vague. We need context in order for these questions to have any sense that is worth considering.

What Humanism Entails

Before delving into the main problem concerning the humanist way of life, it is worth recapitulating its foundations. As briefly discussed in a previous article, humanism is a way of life that has no specific origin; rather, it has developed over thousands of years and it is based upon moral principles that are intended to guide human conduct. These principles are moral in that they are both ethical and logical so as to give humans the best opportunity to survive and to experience happiness. If ethics concerns subjectivity and logic concerns objectivity, then it stands to reason that morality is common sense insofar as humanism can be practiced by nearly anyone. But what it is that we mean when we say “common sense”?

Philosophically, common sense is ambiguous. However, in simple, non-technical words, it is about practicality; more specifically the term itself refers to the simplification of a complex situation so that it becomes manageable, leading to a desirable outcome.1 As such, common sense is “common” because almost anyone can use it to help themselves survive and to experience happiness. The reason for this is because it is dependent upon the use of the senses, e.g. hearing, sight, smell, taste, and touch. We shall now consider a scenario to help us put common sense into perspective.

Scenario 1. The risk of cooking food with an oven

In humanist terms, we know from experience that placing a hand too close and for too long a duration to a source of excess heat, such as a flame, results in an unpleasant burning sensation. Hence, it is common sense that we avoid doing this unless we have a reason to do so. Why might we have a reason for placing ourselves at risk of burning our hand and sustaining an injury? Perhaps we may be cooking a meal in a heated oven that requires us to hold a dish containing our meal. Therefore, according to common sense, in order to avoid burning our hand(s), we cover them with a material, e.g. kitchen mittens, to allow us to hold the dish safely and minimize the risk of injury. In such a situation where relatively little complexity is involved, the procedure is straightforward.

Although this scenario is highly simplistic, it is nonetheless humanistic insofar as it concerns a problem and its solution. In this situation the problem is the risk of being burned by the heated oven and its solution is the kitchen mittens that offer hand protection, minimizing the risk of injury to our hands. Thus, humanism entails in simplifying the complexity of our surroundings, and hence, our environment so as to encourage human survival and well-being. But how do we respond to a situation that is more complex?

The Problem with Humanism

The humanist approach to life has arguably proven to be successful over the millennia. However, it is has an important limitation. We will now consider another scenario, albeit one that is more complex than that covered in the previous subsection.

Scenario 2. The dilemma of an agriculture business

Let’s imagine we are working in a commercial field that is used for agriculture. In this field, we are growing a variety of fruit such as apples and apricots, including vegetables such as lettuce and potatoes. But there are some problems that are affecting our ability to grow our fruit ; our produce is being invaded by aphids, which the agriculture industry views as pests. In response to this, we apply a pesticide in order to deter them from invading our produce. After having observed the condition of our fruit trees over a period of several days, we notice that they are being attacked far less frequently than before. It appears that our application of the pesticide has worked.

Another problem that we must address concerns our vegetables. Due to time limitations we must use tractors to maintain the necessary productivity that will ensure that our agriculture business is profitable. From experience, we find that it is more economical, hence, less costly to use tractors than to rely on the manual labor of human beings. The use of such machines allows us to grow more crops per unit time than would have been possible otherwise.

As far as we can observe with the naked eye, our business seems to be operating smoothly and is maintaining profitability. However, what we do not realize is that because our agricultural approach is so reliant on toxic chemicals and technical equipment that even though we are able to maintain a relatively high level of productivity, we are doing so at the detriment of the environment. Further, we are not even aware how the damage we are committing to it may be affecting our well-being, including that of our surrounding communities. How can this be?

If we observe critically at the use of the pesticide, we notice that it does indeed act as a deterrent against the above-mentioned pests. However, because the fruit and the lettuce are now contaminated this means that the people who eat them will be prone to ingesting pesticide residue, unless they wash the produce thoroughly. Some research shows that the use of pesticides can increase the risk of certain diseases2, including cancer.3 Aside from this concern, there is also the issue of how the use of the pesticide may affect the environment. For instance, the use of liquid pesticide can seep through the soil potentially killing the countless number of microorganisms that inhabit it, some of which are beneficial for plant growth by helping plants to absorb ammonia through nitrogen fixation.4 In addition, pesticide residues can percolate into nearby groundwater stores, contaminating them and potentially endangering the health of surrounding communities that rely upon this water for domestic consumption.5 Another issue is that the use of the pesticide can over time negatively affect bee populations that help to pollinate our fruit trees. In particular there is a strong possibility that our apples may be lesser in both quantity and quality as the bees will not be able to pollinate them as effectively due to contamination.6-7 Apples are highly dependent upon bees for their continued growth and survival, which is why this is a problem.

Aside from such concerns, we must also consider the effects of our reliance upon tractors for ploughing the soil of our field, which is problematic due to their sheer weight. Their use leads to excessive compaction of the soil, which means that the roots of our crops struggle to grow and extract the water and nutrients they need, which in turn means that our lettuce and potatoes are not able to grow optimally.8 The result is that they are more prone to disease and stunted growth.

Here, we are presented with a dilemma; we have an agriculture business that is almost completely reliant on chemicals and industrial machinery for its economic survival. However, we have little awareness of the long-term repercussions of our activities and how they may affect the environment and surrounding communities. Such is the nature of our business that in our limited awareness, we can only thrive by solving problems through technical intervention, e.g. the use of pesticides for deterring pests, and the use of tractors for improving productivity. This is what “common sense” encourages us to do within the confines of the capitalist system, which in every direction incentivizes us to find relatively simple and quick-to-apply solutions without considering their long-term social and ecological consequences.

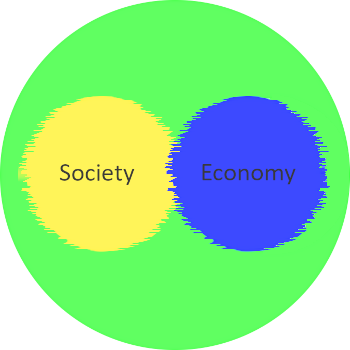

Figure 1 helps to put this scenario into perspective. Theoretically, humanism does not include the component of ecology in its morality. It is for this reason why the green circle representing the ecological component is unlabeled; because humanism does not give it equal recognition as the other circles symbolizing the components for society and the economy. The effect of this is that social and economic collapse becomes increasingly apparent in the long-term future. This is why their respective circles appear distorted. Viewed this way, the component for ecology is situated in the background, and is treated merely as an afterthought rather than a priority that is central to human survival and well-being.

The underlying problem with humanism is that the common sense that comes with it is limited insofar as its value system is concerned. Although humanism has undeniably helped humans to thrive beyond survival, its value system is questionable as it does not emphasize the interdependence of all organisms between themselves and their environment. Therefore, it is limited in a practical sense with the addition that it does not foster enough of an emotional appreciation for the environment so as to help humans feel a connection to everything that makes up their home planet. In this sense, to “feel” means to acquire information through all the senses and to make a judgment about what to do with one’s life in relation to one’s surroundings. As such, it is foolish to pursue an activity without it having an ecological basis because otherwise it leads to the dilemma featured in scenario 2.

Ecohumanism as a Viable Alternative

Moving beyond humanism and its anthropocentricity requires us to change our approach to life. In other words, our way of thinking and behaving is what needs to evolve. In an article where they introduce the concept of ecosocialization, Sami Keto and Raisa Foster state the following, which helps to clarify what this means:

Adapting to human set conditions and limits is, of course, not enough, but we

have to adjust our lives to nature’s cycles and ecosystem capacities. Importantly,

while human set limits are always open for negotiations, the nature set ones are

not; that is why we need to show more conformity in adjusting to ecological

conditions.9

In this context, the common sense of the past is no longer appropriate for human survival and well-being in the future. What we need is to develop a philosophy that is more critical, and more appropriate for responding to change.10 What might this look like in concept?

Figure 2 illustrates the convergence of the social, economic, and ecological components, which is in accordance to ecohumanism. At the center, we find a glowing white spot, signifying the awareness of an individual, which conceptually expands into the component circles for society, economy, and ecology. This figure is shaped somewhat in the form of an eye, which signifies that it is a vision that is integral to human existence. The alternative is a lack of vision, which translates into a lack of understanding of how humans are intricately connected to the environment, bearing in mind that an environment is the sum total of our surroundings including the animate (organisms) and the inanimate (air, land, and water).11

The vision that ecohumanism affords is one that is more balanced, and therefore, it may be viewed as a viable alternative to that of humanism. What we have established is that there is a need for our way of life to be more critical and more sensuous. To expand our comprehension of what this means, we shall briefly return our attention to scenario 2.

Let’s consider the dilemma of the agriculture business previously considered. On the one hand, as professional agriculturists, we have the responsibility of making a profit in order to survive. If we do not do so, we will find ourselves in an economically disadvantaged position as a result of not having enough finance to purchase the resources we need to survive. Such resources include but are not limited to: water, food, clothing, shelter, and transportation vehicles. On the other hand, our limited awareness is leading us to behave foolishly due to our lack of understanding as to how the technical interventions we are employing to improve our productivity in the field is leading to the gradual degradation of the environment, including that of our surrounding communities. Yet, as we are not able to perceive this, we pay no attention to it. Here, the role of our perception and emotion is important to reflect upon as they directly relate to the morality of ecohumanism. We shall analyze this in order to gain greater clarity in our vision.

The study of consciousness, and more specifically of phenomena such as emotion and perception is in general what phenomenology is about.12 As previously suggested, ecohumanism may be viewed as a viable alternative to humanism. This is primarily because it is more critical and more sensuous, which is the result of its value system that emphasizes ecology as a factor that is central to human existence. With that said, in order for us to embody ecohumanism, we must allow ourselves to feel through our senses, which will subsequently permit us to experience emotion while relating to our surroundings so that we may develop a connection to them.

The above-mentioned may be easier said than done; we cannot evade the fact that subjectivity forms a part of the process of becoming connected to the environment. Establishing this connection requires learning not only how to observe, but also how to feel. The latter in particular is only vaguely understood relative to the former, yet it is highly important in contemporary time and from a Western perspective. It is especially important mainly because of the way that science has progressed since the Enlightenment (a.k.a. the Age of Reason), which is as such that it has spurred distrust of the human senses, and subsequently of feelings and emotions, in favor of reason and measurement.13-14 The culmination of the work produced by some of the greatest philosophers and scientists at the time has been, somewhat ironically, to erect a dichotomy between humans and the environment. This dichotomy arose partly due to the belief that humans are the dominant lifeform and are therefore superior to all other organisms, and partly because there was a growing desire to improve the living conditions of people. Thence, a justification existed for subordinating all aspects of the environment solely for human use.15

In accordance to ecohumanism, the dichotomy between humans and the environment is either minimal or nonexistent. In this way, we learn to interact with the environment with more deliberation and passion. Common sense guides us away from treating the environment merely as an object that is separate from us, but rather as our extensional home that requires the same kind of care that a house or shelter provides us with. Rather than viewing the environment as an entity that is to be exploited and that requires taming, we instead feel happiness and a sense of gratitude not merely for what it provides us with, but also for its existence in and of itself, that is, its aesthetic appeal. However, cultivating such an emotional connection cannot happen on its own. It must also combine with careful analysis of our own feelings, emotions, and thoughts so that they can be placed in a context that is more appropriate both for maintaining the integrity of Earth’s ecosystems and for sustaining our existence.

Let’s reassume the position of the agriculturist from scenario 2, except this time, let’s imagine that we embody the ecohumanist philosophy. In such a context, we will have learned that it would be unwise to make any alterations to the environment without having an awareness of their social and ecological implications. In addition, we would have learned that it would be more economical, that is, less costly to design our agricultural field holistically so that it is configured to address the root cause of our problems. However, we would also be aware that money cannot be the only measure of value, given that natural resources and ecological carrying capacity are what determine our ability to survive. Further, in phenomenological terms, we notice that our feelings and emotions extend outward into Earth’s ecosystems, and our perception becomes broader yet more acute when it comes to noticing patterns and relationships in nature.

At this point, it is worth considering the design system of permaculture, which as its name implies is about combining “permanent agriculture” and “permanent culture” by working with nature in a manner so as to benefit not only humans, but all lifeforms included.16 Through permaculture design, we have an awareness that it would be more effective and efficient to reconsider the use of our agricultural land and design it so that ecosystems rather than pesticides and industrial machinery do the work for us. As such, permaculture concerns the development of a way of life where humans live in harmony with all other organisms and are able to meet their survival needs by using, reusing, and recycling Earth’s natural resources, all the while living at or below ecological carrying capacity. In simple terms, it is “sustainable” in almost every sense of the word and the science demonstrating this exists.17

The design system of permaculture represents an ecohumanistic way of life; this is one of the reasons why it deserves a mention. Another reason is to underline how, as with ecohumanism, it is currently in its stage of childhood as it is in a growth phase, which is similar to the state of science at the start of the 21st century.

To put the above-mentioned into perspective, let’s suppose we are studying the geography of our agricultural field from scenario 2 for the purpose of redeveloping the landscape. In this situation, one of the first things we would do before making any changes to our field is that we would form a plan. This plan would help us to visualize how we would like it to appear, and how we may configure our crops and trees so that they grow optimally while also ensuring that we cater for the habitat and nutritional needs of animals so as to encourage biodiversity. The goal is maximum efficacy and efficiency not only for the sake of sustainability, but also for human enjoyment. Therefore, our plan has practical and aesthetic considerations. However, there is something else that we must do before we even begin planning the redesign of our field. What might this be?

Pragmatically, redesigning our way of life requires that we begin by reflecting upon our own selves regarding what we value and how we would like to live. Beginning this process of change is possible by asking ourselves questions through rhetoric in relation to our surroundings. Here’s a set of questions that relate to this, bearing in mind that the angles in which we may approach this topic are so numerous that we could write books about them!

- What do I feel when I think about the environment and my relation to it?

- Is my morality premised upon ecological principles, and if so, to what degree?

- What are the genetic and environmental factors that have led me to become who I am today?

- If I reflect upon the meaning of the word “home”, what do I visualize?

- Does my emotional state change in accordance to my geographic location, and if so, then why?

- When I reflect upon Earth’s ecosystems in what ways do they provide me with value?

- Do I care about plants and animals that do not bring me any apparent and immediate benefit to my life, and if so, then why?

- How do I feel when I walk through a field or garden containing a variety of plants and trees that harbor birds, insects, and worms?

- In what ways is science and technology shaping the evolution of urban areas (e.g. towns and cities), and concurrently, how is this affecting humans and other animals?

- If I were to envision humanity’s future in the 21st century and beyond, what would it look like and why?

To conclude, if we wish to improve our chances of survival and well-being, we must not only focus on ourselves but also on the interaction between ourselves and our environment that gives us life. To put it another way, we may view ecohumanism as being more “human” than humanism itself as it reconnects us to the spatiotemporal context that enables our existence and which forms the basis upon which we can survive, evolve, and improve our standard of living. It is for this reason why humanism is an outdated philosophy.

References

1 Rosen, S., 1966. Common Sense. The Journal of General Education, 18(2), pp.112-136.

2 Kim, K., Kabir, E. and Jahan, A. S., 2016. Exposure to Pesticides and the Associated Human Health Effects. Science of the Total Envionment, 575, pp.525-535.

3 Bassil, K. L., Vakil, C., Sanborn, M., Cole, D. C., Kaur, J. S. and Kerr, K. J., 2007. Cancer Health Effects of Pesticides. Canadian Family Physician, 53, pp.1704-1711.

4 Poudel, S., Poudel, B., Acharya, B. and Poudel, P., 2020. Pesticide Use and its Impacts on Human Health and Environment. Environment & Ecosystem Science, 4(1), pp.47-51.

5 See reference 4.

6 Khalifa, S., Elshafiey, E., Shetaia, A., El-Wahed, A., Algethami, A., Musharraf, S., Al Ajmi, M., Zhao, C., Masry, S., Abdel-Daim, M., Halabi, M., Kai, G., Al Naggar, Y., Bishr, M., Diab, M. and El-Seedi, H., 2021. Overview of Bee Pollination and Its Economic Value for Crop Production. Insects, 12(8), p.688.

7 Museum of the Earth. 2022. Bees and Agriculture. Available at: https://www.museumoftheearth.org/bees/agriculture.

8 For more information, see the following link: https://extension.umn.edu/soil-management-and-health/soil-compaction.

9 Keto, S. and Foster, R., 2021. Ecosocialization – an Ecological Turn in the Process of Socialization. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 30(1-2), p.44. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09620214.2020.1854826.

10 Patterson, T., 2016. Too much Common Sense, not Enough Critical Thinking! Dialectical Anthropology, 40(3), pp.251-258.

11 I mention the animate and the inanimate in such a manner purely for the purpose of distinguishing them, which helps in identifying them.

12 The Encyclopedia Britannica offers a clear and concise description of phenomenology. The following link provides more information: https://www.britannica.com/topic/phenomenology.

13 The Encyclopedia Britannica offers a brief description of the Enlightenment, which is useful for obtaining a general idea about what it is. The following link provides more information: https://www.britannica.com/event/Enlightenment-European-history.

14 Micahel A. Peters has authored an editorial article entitled “The Enlightenment and its Critics”, which briefly discusses criticism of how the Enlightenment is perceived among academics. His article is useful for obtaining a more nuanced understanding about what it constitutes. The article is accessible through the following link: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00131857.2018.1537832.

15 Kopnina, H., 2019. Human/Environment Dichotomy. In: The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology. John Wiley & Sons.

16 Permaculture Research Institute. 2022. What is Permaculture?. Available at: https://www.permaculturenews.org/what-is-permaculture/.

17 Krebs, J. & Bach, S., 2018. Permaculture—Scientific Evidence of Principles for the Agroecological Design of Farming Systems. Sustainability, 10, 3218. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093218.